A closer look at the embroidery on the small motifs in the hunting scene on the Bacton Altar Cloth

Across the middle of the Cloth, there appears to be a scene taking place which was the height of aristocratic pursuits during the medieval and Early modern period – the Hunt. The scene includes a number of different animals, including quarry and hounds, and a huntsman.

The Bacton Altar Cloth was embroidered before the documentation of techniques or the definition of individual stitches. As modern embroiderers, we have easy access to stitch compendiums and numerous publications dedicated to single techniques. These provide specific step by step instruction, resulting in widespread uniformity of stitches and techniques. In the 16th and 17th centuries we do find that embroidery is often mentioned in contemporary documents, for example cutwork or use of silk in diverse colours, but there is little definition of what a specific stitch is or how to work it. Some appear obvious and we still know these stitches today – for example, chain, stem and couching – while others are not as readily identified.

We have been examining the stitches used to determine how this set of motifs were worked and to try and understand the techniques the embroiderers used. Given the circumstances around Covid restrictions, we are lucky to have high quality photos of both front and back to work from. Obviously, we would much rather be working from the real article!

We begin with the only human figure (right) in this series of motifs: The Huntsman. His blue coat is worked with silk floss in block shading. The silk is very lightly twisted and thicker than we generally use now. He carries a hunting horn and a spear/pike worked in Venice Gold, couched with yellow silk. Venice gold is a silk core wrapped in a thin, narrow strip of gold which is now commonly known as filé or passing thread.

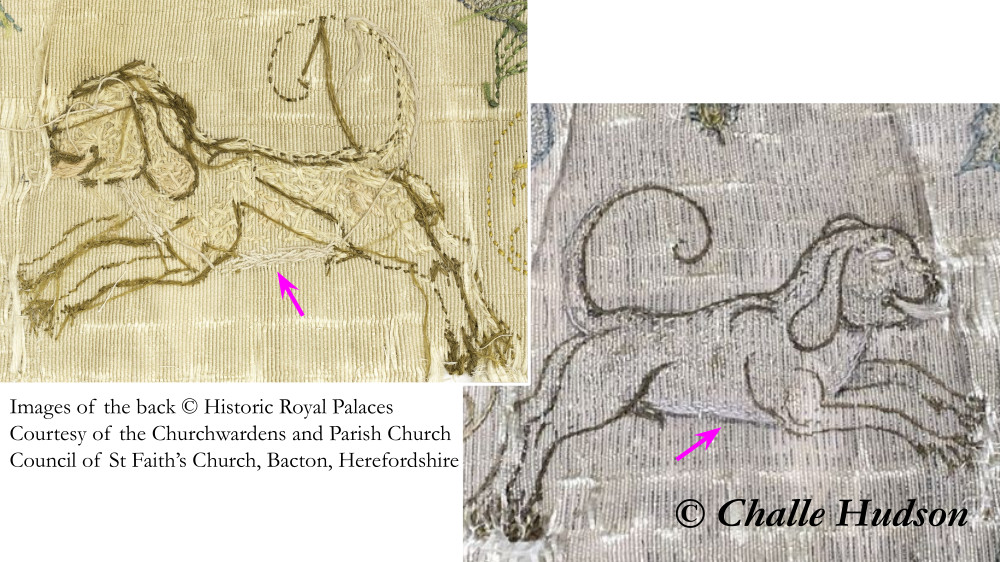

On first impression, this hound (below) is just an outline image – was he meant to be filled in and hasn’t been? On closer inspection, we can see white stitching on the front which is confirmed when we look at the back. There appears to be white highlights and shading on his belly but the dark outline along the lower edge has no evidence of stitching. Could it be the embroiderer’s pattern line?

The sprightly greyhound (below left) has some directional stitching, but it largely falls top left to bottom right. However, a greyhound has very short hair with little texture.

The marten (below middle) and bear (below right) have evidence of unstructured long and short stitches, and there is some evidence of split stitches. This diversity reflects the rough, wild nature of their fur. The marten has some vertical stitching on his back and neck, but his tail is very bushy and the slightly longer stitching may have been used to indicate the longer fur. The bear certainly has directional stitching across his back and shaping down into his tummy, and much longer stitches giving the impression of a nice long, thick coat.

There are three deer in the series, presumably the objective of the event. The stitches are again satin and long and short stitch with evidence of split stitches. Shorter stitches appear to be used overall to indicate the shorter pelt of deer. There are different directions used on the bodies of the different deer. The stitches appear straight up and down on the deer on the left. In the centre, a few directional stitches are introduced.

The deer on the right is embroidered very differently, with linear rows of stitches following the line of chest and stomach and down the legs. The faces of all three are quite similar with very detailed stitching. They show some evidence of padding, perhaps small under stitches, but it is difficult to establish for certain as it is covered on both sides.

There are several small areas on the first two deer that appear to be devoid of stitching. Fallow deer, introduced to England in the 11th century, have white spots and were kept for both ornamental and hunting purposes. It is unclear what has happened here until we look at the back of the cloth. Here we see evidence of white thread which could indicate that the stitches were there but have, perhaps, disintegrated on the front, or been intentionally removed.

These three deer provide a grouping that, when observed in comparison to one another, raise questions about who may have embroidered these motifs. Are we seeing deer worked by embroiderers with differing skill levels? Are these simply different embroiderers who preferred different styles? Are we seeing a skilled embroiderer teaching a less skilled one? All perfectly reasonable and intriguing questions – but unfortunately no definitive answers.

There are a few mysterious motifs within this Hunting Scene that can be overlooked if you aren’t looking very carefully. For example, you barely discern the outline of this dog (right) but his collar remains intact, worked in gold threads. The rest of him is simply a shadow on the silk fabric which shows the disturbance caused by the stitches and maybe some of the embroiderer’s pattern markings.

Even less obvious is this motif (left). We have dubbed him a lion, and except for the few remaining stitches on the tail and a little more on the back we may not have been sure he ever existed. It is clear is that the tree was stitched over the animal and it is unlikely the silk has just disintegrated. Hence, the mystery remains: were these “ghost” motifs unpicked, and if so, why?